| ||

|

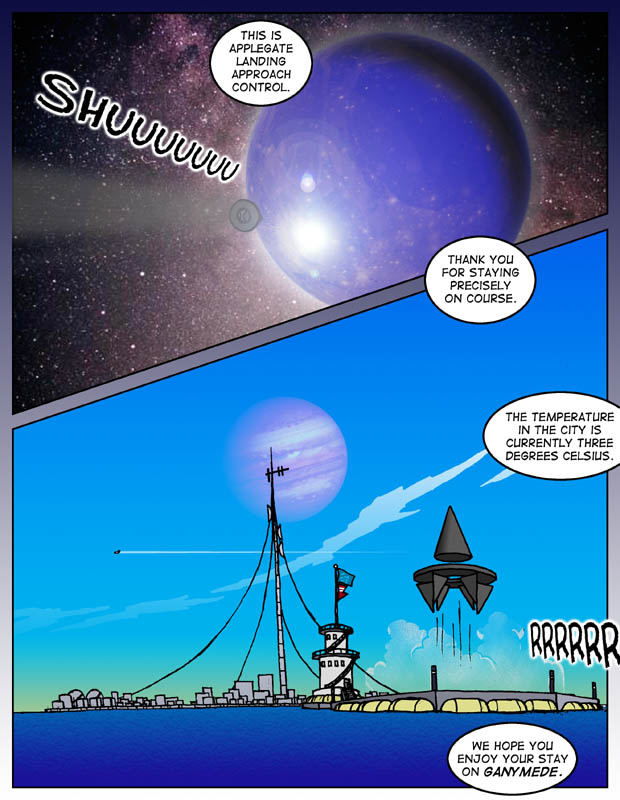

(Jon sez:)  Ganymede in 2148 is mostly terraformed, covered in a fresh-water ocean

several hundred meters deep as the satellite's ice melts. The moon's old

features are visible only as shallow spots in the ocean, showing up as

patches of pale blue-white from space. When the terraforming is complete,

Ganymede's ocean will be many kilometers deep and the surface temperature

will rise as the melting of the planet's ice no longer acts as a heat sink.

Cities such as Applegate Landing float in the world sea like immense river

barges, each made up of numerous hexagonal plates. Large shuttles are

diverted to a landing pad which is towed behind the city so that, in the

case of an emergency, the shuttle doesn't plunge through a plate and sink

part of the city.

Mark has commented to me that we haven't received much email lately, and he

is correct. This is a shame, as the only way the two of us know if our

storytelling is working is if we receive feedback from our readers. Well, from

readers other than our friends and relatives.

Ganymede in 2148 is mostly terraformed, covered in a fresh-water ocean

several hundred meters deep as the satellite's ice melts. The moon's old

features are visible only as shallow spots in the ocean, showing up as

patches of pale blue-white from space. When the terraforming is complete,

Ganymede's ocean will be many kilometers deep and the surface temperature

will rise as the melting of the planet's ice no longer acts as a heat sink.

Cities such as Applegate Landing float in the world sea like immense river

barges, each made up of numerous hexagonal plates. Large shuttles are

diverted to a landing pad which is towed behind the city so that, in the

case of an emergency, the shuttle doesn't plunge through a plate and sink

part of the city.

Mark has commented to me that we haven't received much email lately, and he

is correct. This is a shame, as the only way the two of us know if our

storytelling is working is if we receive feedback from our readers. Well, from

readers other than our friends and relatives.

|

(Mark sez:)  Ah, yes: terraforming -- the art of making a planet habitable for humans. Barring

any unexpected

surprises,

we can be reasonably confident that, pretty as all those sparks moving about our

solar system are, they are all completely dead -- inert lumps of rock, ice, and gas.

This is of course completely unacceptable. Fortunately, the ability to do something

about it is well within

our reach. It's only a question of whether we have the confidence in ourselves to

build new homes for life

out in the universe.

Ah, yes: terraforming -- the art of making a planet habitable for humans. Barring

any unexpected

surprises,

we can be reasonably confident that, pretty as all those sparks moving about our

solar system are, they are all completely dead -- inert lumps of rock, ice, and gas.

This is of course completely unacceptable. Fortunately, the ability to do something

about it is well within

our reach. It's only a question of whether we have the confidence in ourselves to

build new homes for life

out in the universe.

Terraforming is a popular subject in science fiction, given that it allows writers to recreate the bustling, life-filled Solar System of '30s and '40s pulp SF without sacrificing too much scientific accuracy. Terraformed worlds in our solar system are seen in the anime and manga series Cowboy Bebop (which also features a waterlogged Ganymede, coincidentally) and Venus Wars. On the literary side, terraforming is the subject of Kim Stanley Robinson's famous Mars trilogy and plays a major part in the climax of Stephen Baxter's Moonseed. Although Baxter's science is a bit, ah, shaky ("hopeful" might be a better term for it, as the terraforming is done in an instant courtesy of a lucky nuclear strike on an ice deposit at the Moon's south pole) the image of Earth's Moon covered with forests and canals is still one of the most romantic things I've ever seen on the printed page. |

|